We’ve lost many years of potentially important research on the use of cannabis as medicine because of polarized views of the ‘weed’ among researchers, policy-makers and the general public.

We’ve lost many years of potentially important research on the use of cannabis as medicine because of polarized views of the ‘weed’ among researchers, policy-makers and the general public.

On one side, there are those who see cannabis as a dangerous psychoactive drug that should be prohibited. On the other, there are those who view cannabis as panacea with the potential to treat every disease and condition known to humankind.

So now that cannabis is legal to smoke, will bureaucratic hurdles still make it hard to study?

It’s time to remove the barriers to cannabis research. There’s still too much we don’t know – both potential benefits and risks.

Cannabis has some promising medicinal properties and its use as a possible anti-convulsive has a long history. New research from my colleagues and myself indicates why it may be effective.

Cannabis originated in the Himalayas and was first cultivated in China for seed and fibre production. Early records of using cannabis medicinally can be traced to Sumerians records around 1800 BC that mention using this plant against a variety of diseases, including convulsions. There are more recent records of cannabis use against epilepsy in Islamic literature.

During the 20th century, the use of cannabis became illegal in many parts of the world due to its psychoactive (“high”) effects. These legal constraints made understanding the chemistry elusive until the 1960s.

It took over 20 years to determine how one of the main cannabinoids – ∆9-tetrahydrocannabinol, more commonly known as THC – causes its well-known effects, such as excessive anxiety and euphoria. THC is also reported to be an analgesic (an agent that acts to relieve pain), a muscle relaxant and an anti-inflammatory agent. This is where cannabis becomes interesting for medicinal use.

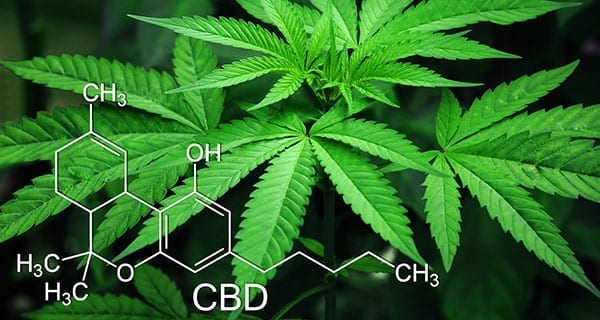

However, because of its noteworthy “high” effects, THC may not be an ideal therapeutic compound despite its potential benefits. Fortunately, there are other cannabinoids that may have the same effects as THC without its psychoactive properties, such as cannabidiol (CBD).

The research on CBD so far is promising. And my colleagues and I recently published a study that may explain how and why it works. Our study shows CBD can reduce the activity of sodium channels in the brain that may contribute to a significant reduction in seizures in those with Dravet syndrome, a severe form of childhood epilepsy that causes frequent and unstoppable seizures, in extreme cases, as many as hundreds of seizures a week.

The good news is that in addition to THC and CBD, there are over a hundred other cannabinoids and related compounds that can be isolated from cannabis. Many may also prove to be promising for specific medical disorders.

The bad news is, unfortunately, our knowledge about most of these other cannabinoids is even more limited than THC and CBD.

If there are therapeutic gems hidden in cannabis that can help the quality of life in some patients, we should consider researching all of them.

So what’s slowing down the science?

In the past, obtaining cannabinoids for research purposes required applying for an exemption from the Controlled Drugs and Substances Act, which could frequently take several months to process. Still more hurdles are required if the cannabinoids are imported from outside Canada.

Under the new system, cannabis researchers are required to apply for a licence under the Cannabis Tracking and Licensing System, which already warns of “several months” for processing.

Sounds like the same bureaucracy, different name.

To put this in perspective, it took my colleagues and I 10 months to acquire 100 milligrams of CBD the first time we applied.

Progress in the cannabis research field would greatly benefit from a reduction in the bureaucratic process involved in obtaining cannabinoids.

The downstream effect could be a more efficient discovery of compounds that would, in turn, potentially extend and enhance the lives of those who suffer from life-threatening conditions.

Mohammad-Reza Ghovanloo is a PhD candidate in the Department of Biomedical Physiology and Kinesiology at the Faculty of Science at Simon Fraser University and a Research Fellow at the Department of Cellular and Molecular Biology at Xenon Pharmaceuticals. He’s a Contributor with EvidenceNetwork.ca based at the University of Winnipeg.

The views, opinions and positions expressed by columnists and contributors are the author’s alone. They do not inherently or expressly reflect the views, opinions and/or positions of our publication.