Although the British car industry wrestled itself to the ground in the 1980s, English sports cars remain a fixture in North America.

There are still plenty of MGs, Triumphs, Austin-Healeys and so on putting along the roads in Canada and the U.S. And well-attended show and shines and picnics are held from coast to coast every year throughout the continent.

Although it may be gone (as a manufacturing industry), the Little British Car (LBC) is not forgotten.

I reckon I’ve owned at least 30 LBCs over the years, and have spent my share of time in and under them. I’ve restored at least a half dozen, spent countless hours tracking down those mysterious electrical glitches and elusive oil leaks, redone an engine or two, and owned at least one of the major marques at one time or another.

I constantly get asked what model(s) I recommend and what neophytes should look for when contemplating entering the wonderful world of English cars.

Though this is far from being a comprehensive rundown of every LBC on the market (Mini, Sunbeam and Lotus aficionados, don’t feel left out), here are some things I’ve learned over the years:

MGB

Not the fastest roadster out there, the B is a tough and surprisingly comfortable two-seater

Not the fastest roadster out there, the B is a tough and surprisingly comfortable two-seater.

As long as you don’t abuse them, Bs can go on forever. But many people, unsatisfied with the performance of their Bs, tend to run the engine too hard. It doesn’t like this and revving it past 4,000 rpm is risky and pointless.

Employ the gearbox judiciously (using overdrive if you have it), take advantage of the engine’s torque, and things will be just ducky.

Things to watch out for include low engine compression, inoperative gauges, wonky front suspension, worn-out kingpins, leaky carburetors and the all-pervasive rust. This last item is the enemy of all LBCs and Bs, by this stage of the game, will have it in abundance if they haven’t been attended to.

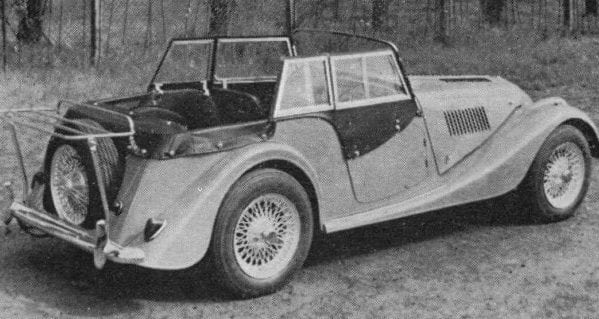

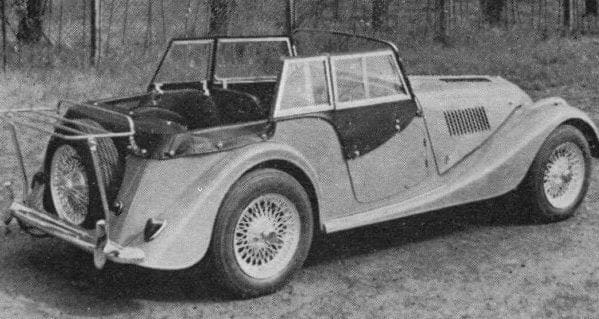

Morgan

Contrary to popular myth, Morgans don’t have a wooden frame. They have a glued ash-wood body tub with sheet metal/aluminum nailed to it

Contrary to popular myth, Morgans don’t have a wooden frame. They have a glued ash-wood body tub with sheet metal/aluminum nailed to it, and a Z section steel frame.

A wide assortment of engines were fitted to Morgans over the years, but the most popular had the redoubtable Standard/Triumph four-cylinder, which was originally designed for use in farm tractors.

Although it’s as tough as old boots, the problem with this engine is that it’s inordinately heavy and can crack the frames of older cars, which can lead to body sag and a wonky drivetrain.

Ford Cortina engines – especially the Kent “crossflow” unit – provide almost as much power and are considerably lighter. Not to mention being easier to service.

The Rover V8-engined Plus 8, meanwhile, was one of the fastest and most nimble LBCs ever made and is still a favourite with club racers everywhere.

Things to watch for with all Moggies: cracked frames up near the engine mounts and at the rear suspension, rotten wood around the door frames, inadequate engine cooling, rusted-out bulkhead and scuttle, worn-out front suspension, engine blow-by, and rusted out frame cross-members.

If you’re looking, try to get one that still has its side curtains and a useable top, and ignore the “St. Malvern’s Palsy” front-end vibration at 100 km/h.

Austin-Healey

Timelessly beautiful, the ‘big’ Healey has skyrocketed in value and pristine ones can fetch $100,000 and more

Timelessly beautiful, the ‘big’ Healey has skyrocketed in value and pristine ones can fetch $100,000 and more. That said, they’re high-maintenance cars and you need to watch out for rusted-out frame and outriggers, corroded body components, worn-out engines, tired front suspension, shot gearboxes, stripped rear wheel splines, and clapped-out exhaust systems.

Six-cylinder Healeys are also uncomfortably hot to drive in the summer. And they leak everywhere in the rain, including up through the floorboards and through the windscreen.

Triumph

To many enthusiasts, this marque is the quintessential LBC and it came in a range of sizes and shapes.

Problem areas include a fragile gearbox and no first-gear synchro with the TR2 and 3, wretched weatherproofing, wretched rustproofing, overheating issues, a fussy clutch mechanism with the TR6, hard-riding suspension with the TR4, disappointingly inferior handling with the 2, 3 and 4, problematic rear suspension with the 4A and 6, treacherous rear suspension with the Spitfire, notoriously hard-to-diagnose wiring problems, rusty rear frame sections, front-end wobble, and Stromberg carbs that, once they let go, are almost impossible to get right again.

Other than that, they’re fine.

Despite its sketchy reputation, the LBC can actually be quite dependable. I have only been stranded a few times over the years and, if you take care of it, the LBC will return the favour.

You can also upgrade your LBC with new-fangled gadgets such as electronic ignition, after-market cooling fans, Weber carburetors, and halogen headlights. But even with these add-ons, you can’t ignore basic maintenance and have to keep an eye on things. Unlike the Universal Japanese Car (UJC), the LBC doesn’t like being ignored.

That accounts for its charm – and partially explains its demise.

Ted Laturnus writes for Troy Media’s Driver Seat Associate website. An automotive journalist since 1976, he has been named Canadian Automotive Journalist of the Year twice and is past-president of the Automotive Journalists Association of Canada (AJAC).

The views, opinions and positions expressed by columnists and contributors are the author’s alone. They do not inherently or expressly reflect the views, opinions and/or positions of our publication.

This site is Powered by Troy Media Digital Solutions