As our world deals with the coronavirus pandemic, a couple of interesting personal stories came out of Europe on March 29.

As our world deals with the coronavirus pandemic, a couple of interesting personal stories came out of Europe on March 29.

The Guardian reported that Hilda Churchill, a 108-year-old woman in Salford, England, became (quite likely) the oldest British person to die from COVID-19 symptoms.

And Turkey’s Anadolu Agency and Fox News reported that a 101-year-old man living in Italy, identified as Mr. P, recovered from the coronavirus.

What’s fascinating about these two individuals is both lived through COVID-19’s elder virus brother, the Spanish flu.

That’s pretty rare. Statista.com approximates there are slightly more than 570,000 centenarians in the world, out of a global population of about 7.5 billion people.

Hong Kong has the world’s longest life expectancy at 84.7 years, according to the United Nations Development Programme’s 2019 survey. That’s followed by Japan (84.5 years), Singapore (83.8 years) and Italy (83.6 years). Canada ranks 14th at 82.3 years.

Hence, most people walking the face of the Earth in 2020 haven’t had to experience two of the world’s worst pandemics.

The Spanish flu was particularly nasty. It occurred between January 1918 and December 1920, and was classified as Influenza A virus subtype H1N1. That’s the same strand contained in the swine flu of 2009. (I’m part of the estimated 11 to 21 per cent of the world’s population who contracted the swine flu, an awful disease, and it took me close to a month to fully recover.)

But the Spanish flu was much deadlier than the swine flu in terms of its total spread and destruction.

No one is exactly sure where the Spanish flu originated. The general consensus is the starting point was the large British hospital and troop staging camp in Étaples in northern France. The terrible battlefield and trench conditions of the First World War, combined with pig and poultry farming in the area, may have been contributing factors.

There has been some suggestions that the cause may rest in the United States. This is due to a significant influenza outbreak in Haskell County, Kansas, in January 1918, which is the Spanish flu’s starting point.

It’s also been theorized that European armies may have carried the disease unnoticed for months or years during the war.

Why was it called the Spanish flu?

Just around the time the Armistice of Nov. 11, 1918, was signed that ended the First World War, the virus began to spread from France to Spain.

The media, which was aware of the disease, began to switch its focus and resources to reporting about growing health concerns in Europe. The escalating numbers in Spain became a primary source of reporting and the infectious disease became associated with that country in an historical context.

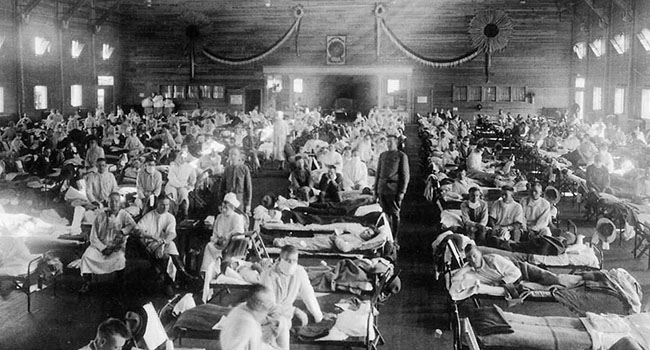

The Spanish flu spread like wildfire.

When people sneezed or coughed in closed quarters during that two-year period, they opened the doors wide for others to get it. Young adults faced the largest number of casualties, with 92 per cent of the cases involving those aged 65 or under.

The flu spread the most in summer and fall, which is unusual, since influenza usually hits the hardest in winter.

A second wave of the deadly virus was even worse than the first.

An estimated 500 million people contracted the Spanish flu, and the death toll was between 17 million and 50 million. It was not quite as bad as the Black Death (1346-1353), which wiped out 30 to 60 per cent of Europe’s population and reduced the entire world’s population by an estimated 75 to 100 million people. But it was still a stunning and terrifying spread of an infectious disease.

The coronavirus hasn’t reached those levels, thank goodness. There were 766,336 active/presumptive cases, 36,873 deaths and 160,001 recoveries as of March 30. If testing was more widely available throughout the world, the actual number of cases would likely be much higher.

Nevertheless, one can safely assume that Spanish flu survivors like Hilda Churchill and Mr. P would have preferred not to have faced a second round of a global pandemic in their lifetime.

Michael Taube, a Troy Media syndicated columnist and Washington Times contributor, was a speechwriter for former prime minister Stephen Harper. He holds a master’s degree in comparative politics from the London School of Economics.

The views, opinions and positions expressed by columnists and contributors are the author’s alone. They do not inherently or expressly reflect the views, opinions and/or positions of our publication.