Members of a University of Alberta student club are walking on air after testing samples of bioengineered knee cartilage in a reduced-gravity experiment competition.

Amira Aissiou and Kirtan Dhunnoo of the University of Alberta Space Design Group strapped themselves in and went for a wild ride in the Canadian Space Agency’s Falcon 20 parabolic aircraft to get a closer molecular and genetic look at the development of osteoarthritis in microgravity – the very weak gravity astronauts experience.

“It was amazing – we felt like we were floating, and to be in this kind of lab felt very surreal,” said Aissiou, a medical student in the Faculty of Medicine & Dentistry who will now help interpret the data after the tissue samples are analyzed.

The out-of-this-world flight experiment was part of the Canadian Reduced Gravity Experiment Design Challenge, held this summer at the National Research Council of Canada (NRC) Aerospace Flight Research Laboratory and organized by SEDS-Canada, the Canadian Space Agency and NRC.

(From left) U of A Space Design Group members Amira Aissiou, Rahul Ravin, Shankar Jha, Kinston Wong and Kirtan Dhunnoo stand in front of the Falcon 20 aircraft they boarded to test bioengineered knee cartilage in simulated microgravity. (Photo: SEDS-Canada)

In their hour-long excursion in the skies near Ottawa, the students tested a device created by the team of 10 U of A engineering and medical students and alumni, and operated by project leaders Aissiou and Dhunnoo, who flew with it through 11 cycles of sloping, up-and-down flight that took them in and out of zero gravity.

The carefully constructed unit – which was firmly bolted down on board the jet – contained a valve system and solution-filled syringes used to store and suspend samples of male and female donor knee cartilage. It captured snapshots of any changes to the tissue during the flight.

After recovering from queasy stomachs, Aissiou and Dhunnoo were elated with how the device, which took a year to develop, stood up to the flight and successfully accomplished its mission.

“We didn’t have a place to test it in zero gravity other than on the actual flight, so there was some worry in making sure all of our calculations were right,” said Dhunnoo, a mechanical engineering graduate from the Faculty of Engineering.

“We simulated the conditions on the ground as best we could, and seeing it come together and actually work was just an awesome experience,” he said.

“We’ve now designed an apparatus that can test these specific forms of bioengineered cartilage tissue in microgravity.”

The team hopes their creation can help discover whether the short exposure to zero gravity sends the tissue samples into a state of osteoarthritis, and measure any differences in reaction between the male and female cartilage. Previous studies using simulated microgravity indicate that male and female tissues behave differently, Aissiou noted.

“We want to have a better understanding of why that is.”

Osteoarthritis is a common form of arthritis that leads to a breakdown of joint cartilage and the underlying bone, causing it to start rubbing against other bone. The disease is more prevalent in females than males, with symptoms including joint pain, stiffness and swelling. There is currently no cure.

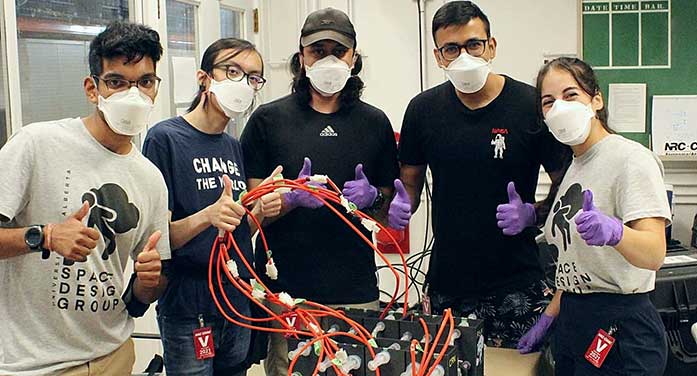

(From left) Rahul Ravin, Kinston Wong, Kirtan Dhunnoo, Shankar Jha and Amira Aissiou with the device they tested as part of a reduced-gravity experiment competition. The device contained secure samples of male and female donor knee cartilage and was able to measure any changes to the tissue samples in low gravity. (Photo: SEDS-Canada)

The cartilage samples were provided by and will be analyzed in part in the lab of Adetola Adesida, a professor in the Faculty of Medicine & Dentistry who also served as faculty adviser to the student group.

The space medicine experiment could build more knowledge in an area that needs more discovery, Adesida noted.

“The impact of space microgravity on bone health is well researched, but not so for cartilage health, which is a tissue of importance in osteoarthritis. The results of the experiment may also provide some insight on the genes and proteins that may be involved in the higher incidence of osteoarthritis in females,” he noted.

“That helps towards the discovery and development of sex-specific drugs to target those genes or proteins.”

“It might even lead to allowing astronauts to stay in space for longer amounts of time,” Aissiou added.

The team is excited about what their pioneering experiment will reveal.

“These were unique samples that had never been in the zero-gravity environment, so we are incredibly optimistic; we know we will see something, but what exactly that something is we won’t know. It will be super interesting, however it turns out,” Dhunnoo said.

The flight also laid potential groundwork for future related experiments, he believes.

“We know what hurdles to expect and have ideas on how to make the logistics of the entire experiment easier to operate, especially for someone like an astronaut who will receive this experiment with limited detailed background, if it does go up into space.”

Collaborating with medical students also gave him a new appreciation for another scientific discipline outside his own field, said Dhunnoo, who now works in the space industry.

“I spent my entire university life working with engineers, so this project was a learning curve to figure out what was required from the medical side. There was a lot of hands-on learning to adapt the experiment to comply and work well with the medical requirements.

“I got some good multidisciplinary experience I wouldn’t have received if this had been purely an engineering experiment.”

The project was funded by the University of Alberta Engineering Students’ Society, the Faculty of Engineering, through Adesida’s lab by the National Research Council of Canada, the Alberta Women’s Health Foundation through the Women and Children’s Health Research Institute, the Canadian Institutes of Health Research, the Cliff Lede Family Charitable Foundation and the University of Alberta Pilot-Seed Grant Program. The project was also supported by SEDS-Canada and the Canadian Space Agency.

| By Bev Betkowski

This article was submitted by the University of Alberta’s Folio online magazine. The University of Alberta is a Troy Media Editorial Content Provider Partner.

© Troy Media

Troy Media is an editorial content provider to media outlets and its own hosted community news outlets across Canada.