Sir Walter Scott and Robert Louis Stevenson’s reputations were created primarily by Hollywood

A recent newspaper feature on people’s early reading experiences reminded me of my own, in which two 19th-century Scottish novelists – Sir Walter Scott and Robert Louis Stevenson – were the key figures. Mind you, they enjoyed a major assist from Hollywood movies.

A recent newspaper feature on people’s early reading experiences reminded me of my own, in which two 19th-century Scottish novelists – Sir Walter Scott and Robert Louis Stevenson – were the key figures. Mind you, they enjoyed a major assist from Hollywood movies.

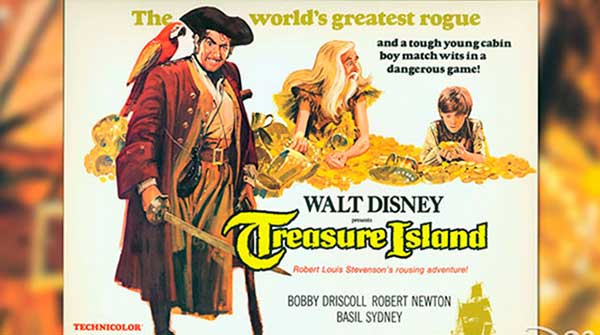

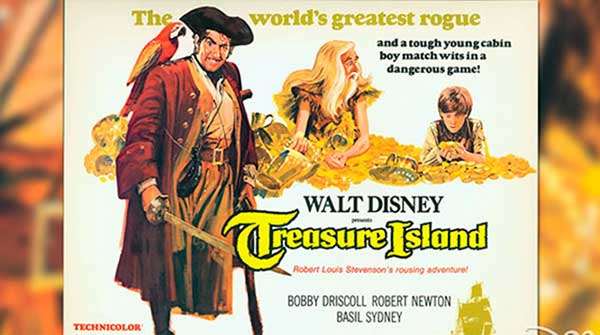

Stevenson came first, when I was seven years of age. The book was Treasure Island, initially published as a magazine serial in 1881-82 and subsequently in full book-length form in 1883. The story of pirates, buried treasure, betrayal and bravery was just the ticket for a seven-year-old’s imagination, and the fact that it was told through the eyes of cabin boy Jim Hawkins was icing on the self-identification cake. I must, however, confess to missing the tale’s moral ambiguity as manifested in the character of Long John Silver.

Actually, it was the 1950 Disney live-action movie that first brought Stevenson and Treasure Island to my attention. Similarly, I was introduced to Scott by MGM’s Ivanhoe, replete with knightly derring-do from Robert Taylor.

But whereas Treasure Island was an easy read, Ivanhoe (1819) turned out to be fundamentally impenetrable. For one thing, its wordiness and archaic style rendered it too dense for my childish brain. And for another, the liberties MGM had taken with the storyline made the book suspect. The problem was simple: What I was reading didn’t quite tally with what I’d seen on the screen. So, somewhere between one-third and one-half of the way through, I gave up, declaring to anyone who’d listen that the book was wrong!

|

| Canada’s Fenian years featured some interesting personalities

|

| Robert Conquest, the man who was right

|

| Divvying up the Middle East after First World War

|

Given their strong narratives and colourful backgrounds, it’s no surprise that the stories of both Scottish novelists served as prime sources for mid-20th century Hollywood. Stevenson-inspired movies included Treasure Island, Kidnapped, The Master of Ballantrae and The Strange Case of Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde, while Scott’s Ivanhoe, Rob Roy, Quentin Durward and The Talisman were all translated – with varying degrees of fidelity – to the silver screen.

That, however, wasn’t all that the two men had in common. Born in Edinburgh some 80 years apart, they were both Tories, although Stevenson had a brief youthful flirtation with socialism. Scott, though, was politically connected in a way that the peripatetic, even bohemian, Stevenson wasn’t.

And that connection renders Scott problematic for modern nationalists, particularly because of his attempt at effecting a reconciliation between romantic Scottish history and the union with England. A particular sore point is his role in organizing the tartan-clad extravaganza that was staged for the famous 1822 royal visit. Succinctly summarising the nationalist indictment, writer and politician Joan McAlpine accuses him of having “perverted and emasculated” the concept of what Scotland is truly about. We can, I think, safely surmise that she’s not a fan!

Scott and Stevenson also suffered from a common malady that often afflicts those who attain great popularity. Although critically well regarded during their lifetimes, their posthumous reputations went into sharp decline, so much so that those who pass judgment on such matters no longer viewed them as serious writers. Instead, they were seen as mere purveyors of stories for children, and perhaps even best experienced via comic book adaptations like those published in the prolific Classics Illustrated series.

Writing specifically about Stevenson’s reputation, Professor Richard Dury describes “a complete reversal of polarity” from positive to negative, ending up with his being “excluded from the canon.” Fame may not always be fleeting, but critical fashion certainly can be!

Still, whatever their deficiencies, it’d be a mistake to dismiss Scottish novelists Scott and Stevenson as no more than tellers of simple-minded children’s adventure stories.

There is, for instance, the aforementioned moral ambiguity that’s particularly prevalent in Stevenson. Indeed, The Strange Case of Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde can be construed as an exploration of moral dualism.

And with its relatively sympathetic treatment of the Jewess Rebecca and her father Isaac, Scott’s Ivanhoe was ahead of the curve with respect to the pernicious nature of anti-Semitism. It was certainly my introduction to the subject.

Then there’s The Talisman, to which the Cambridge historian Jonathan Riley-Smith ascribes much of the credit – or blame – for what he perceives as modern misconceptions of the 12th-century Crusades. From it, we get the popular picture of the noble Saladin juxtaposed against the boorishly greedy crusaders.

For a guy now deemed literarily irrelevant, Scott casts a long shadow.

Pat Murphy casts a history buff’s eye at the goings-on in our world. Never cynical – well, perhaps a little bit.

For interview requests, click here.

The opinions expressed by our columnists and contributors are theirs alone and do not inherently or expressly reflect the views of our publication.

© Troy Media

Troy Media is an editorial content provider to media outlets and its own hosted community news outlets across Canada.