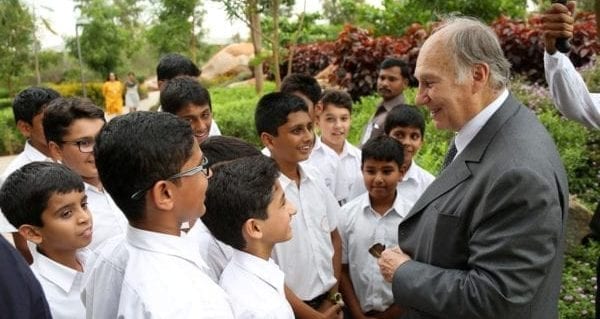

His Highness the Aga Khan meets with students at the Aga Khan Academy in Hyderabad, India.

When your last name is Arab and you’re not a Muslim or terrorist, you defy a few Islamophobic stereotypes yourself.

When your last name is Arab and you’re not a Muslim or terrorist, you defy a few Islamophobic stereotypes yourself.

I’m Arab in name, but my father’s religion is Maronite Catholic – an early branch of the Roman Catholic Church. I was brought up Roman Catholic and indoctrinated in papal infallibility.

So the idea of the Aga Khan, a spiritual leader who represents all of the foibles and eccentricities of us mere mortals, is itself a revelation, never mind the many other ways he smashes stereotypes about Muslims.

The Aga Khan, a direct descendant of the Prophet Muhammad, has a dualistic approach to life. He lives firmly in both the material and spiritual worlds. This duality is reflected in an interview he gave Vanity Fair.

“An imam is not expected to withdraw from everyday life,” he said. “On the contrary, he’s expected to protect his community and contribute to their quality of life.

“Therefore, the notion of the divide between faith and world is foreign to Islam. The imamate does not divide world and faith. That’s very little understood outside Islam.”

Those words embody the Aga Khan, the spiritual leader of 15 million people around the world, including 120,000 in Canada who belong to the Ismaili faith.

Theirs is a peaceful and progressive religion, fuelled by philanthropy to overcome the challenges of everyday life.

Known as His Highness, a title conferred on him by Queen Elizabeth shortly after inheriting the Imamat at 20, the Aga Khan preaches plurality. He has dedicated his life to fighting poverty and has spent a large portion of his wealth building schools and educating millions of children in the developing world.

Much has been made about his philanthropic contributions during his 60-plus years as imam. Indeed, he will make history again this week in Vancouver, when the University of British Columbia and Simon Fraser University confer joint honorary doctorate of laws degrees in a simultaneous ceremony on Friday, Oct. 19, in recognition of his lifelong service to humanity, and his contributions to both institutions.

This comes two days after he is to be awarded another honorary doctorate of laws from the University of Calgary.

The Aga Khan wields Ismaili philanthropy as his leadership’s central mandate to improve the quality of life, not only of his followers but for of all the world’s most vulnerable people.

Tomes have been written about his global charity work and efforts to eradicate society’s ills.

But it’s his approach to human frailties that I find far more interesting.

The Aga Khan has lived all of the trials and tribulations of his followers, including the emotional roller-coasters of love, marriage, divorce and heartbreak.

Because of that, he’s someone who can inspire, teach and relate to me and all my fellow Canadians, regardless of faith.

The Aga Khan builds bridges between people, religions and cultures. He fosters collaboration rather than conflict. And he’s successful in upholding the dignity of human kind because his is a spiritual leadership grounded in reality, and in his own experience of human joys and suffering in all of its forms.

Paula Arab is a Vancouver-based freelance columnist and media strategist. She can be reached at [email protected].

The views, opinions and positions expressed by columnists and contributors are the author’s alone. They do not inherently or expressly reflect the views, opinions and/or positions of our publication.