We tend to think of England and France as historic enemies. But the full historical picture is more complicated

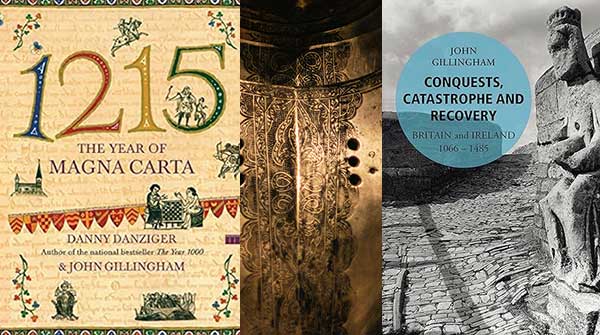

I’ve been dipping in and out of a couple of books from John Gillingham, the historian best known for his modern biography of England’s Richard I (aka Richard the Lionheart). One of these books is Conquests, Catastrophe and Recovery: Britain and Ireland 1066-1485. And the other – a collaboration with journalist Danny Danziger – is 1215: The Year of Magna Carta.

I’ve been dipping in and out of a couple of books from John Gillingham, the historian best known for his modern biography of England’s Richard I (aka Richard the Lionheart). One of these books is Conquests, Catastrophe and Recovery: Britain and Ireland 1066-1485. And the other – a collaboration with journalist Danny Danziger – is 1215: The Year of Magna Carta.

Their thematic organization is what makes the books so casually accessible. Rather than a chronological beginning-to-end narrative, there are chapters focusing on particular aspects of medieval life.

For instance, 1215’s chapter on Tournaments and Battles dismisses the popular cinematic image of massed armies engaging in pitched battles. Sure, it happened occasionally. But such events were relatively rare.

|

| Related Stories |

| The death of King Richard the Lionheart

|

| Was Richard the Lionheart gay?

|

| England’s warrior queen

|

To quote: “Commanders offered battle only when they were confident of the outcome, and in these circumstances their opponent was almost certain to avoid it.” The French king, Philip Augustus, was no novice at the practice of war, but he “fled from Richard I in 1194 and again in 1198, preferring the humiliation and the losses incurred in flight to the risk of total disaster that battle entailed.”

In reality, medieval European warfare was generally a matter of siege, skirmish and laying waste to the other guy’s territory. Destroying the enemy by famine was a cost-effective way of going about business.

We tend to think of England and France as historic enemies. Or if that’s too stark, as distinctly different societies with interests that often diverged. That perception is reinforced by the fact that much of England’s involvement in Europe revolved around diplomatic and military alliances intended to keep imperial France from swallowing the lot.

But, as Gillingham reminds us, the full historical picture is more complicated. For several hundred years, England and France shared an interchangeable ruling class, and their conflicts had to do with the distribution of power and possessions within a culturally homogenous aristocratic milieu. You might even call it a form of civil war.

The French connection began with the Norman Conquest of 1066, as a consequence of which the old English landowning class was almost totally dispossessed and replaced by a new Francophone elite. And this social transformation extended to the religious sphere: “By 1100 not a single bishopric or major abbey was ruled by an Englishman.”

The built form of the physical environment was also impacted. The existing cathedrals and major churches were largely replaced by buildings in the continental style, and large stone castles of French design proliferated. Between the religious and the secular, some of these “were the largest buildings of their kind to be erected north of the Alps since the fall of the Roman Empire.”

After the Conquest, England was ruled by a succession of French aristocratic dynasties, of which the House of Anjou (1154-1216) was the most successful territorially. Dubbed the Angevins, their late 12th-century writ ranged from the Scottish border to the Pyrenees and embraced much of what is now France. This massive agglomeration wasn’t the product of conquering English kings but rather an accumulation by a French aristocratic family that had tacked England on to their inventory of possessions.

Unsurprisingly, conflict with the House of Capet – the French royal house in Paris – was a regular thing. The tide ebbed back and forth. At one point in the early 13th century, the Capetians “came within an ace of becoming kings of England too.” And returning the favour, Edward III claimed the French throne in 1340 by virtue of his royal French mother and the absence of a direct male Capetian heir. Intermarriage rendered it all very tangled.

Eventually, however, the connection withered. With the loss of Calais in 1558, the English monarchy’s last possession in France was gone, and the two countries went their own way, evolving into the very distinct entities we know today.

Still, traces remain on both symbolic and physical levels.

Cast in bronze, the Lionheart’s giant equestrian statue has stood outside the Palace of Westminster since 1860, thus symbolizing the heroic place he holds in English folk memory and legend. The real Richard – the second Angevin king – was actually a Frenchman whose only material interest in England was as a source of revenue.

And then there’s the built form of all those cathedrals, churches and castles. To give Gillingham the last word: “The new regime imposed itself on a gargantuan scale; its mark on the English landscape can still be seen today.”

Troy Media columnist Pat Murphy casts a history buff’s eye at the goings-on in our world. Never cynical – well, perhaps a little bit.

For interview requests, click here.

The opinions expressed by our columnists and contributors are theirs alone and do not inherently or expressly reflect the views of our publication.

© Troy Media

Troy Media is an editorial content provider to media outlets and its own hosted community news outlets across Canada.