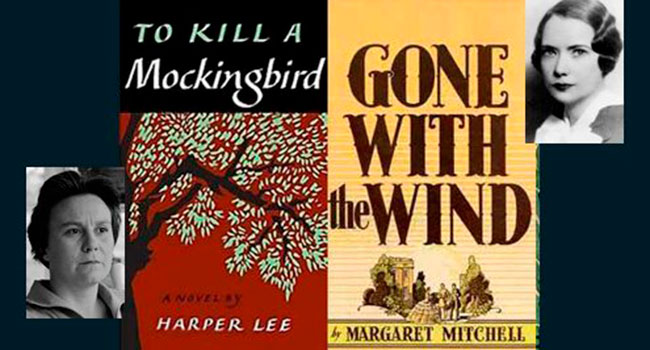

Born 25 or so years apart, Margaret Mitchell and Harper Lee were each defined by a single book. Mitchell’s was Gone With the Wind, while Lee’s was To Kill a Mockingbird.

Born 25 or so years apart, Margaret Mitchell and Harper Lee were each defined by a single book. Mitchell’s was Gone With the Wind, while Lee’s was To Kill a Mockingbird.

Both women – daughters of the 20th century American South – situated their work in their native regions. Mitchell chose Civil War Georgia for her locale. Lee opted for 1930s Alabama.

Mitchell’s book can be described as a southern plantation novel that takes a romantic view of the Old South and the Confederacy. Lee is more critical of her milieu. With racial injustice as one of its primary themes, To Kill a Mockingbird became a symbol of affinity for the mid-20th century American civil rights movement.

Mitchell (1900-1949) was born in Atlanta, Ga., and lived her life there.

Lee (1926-2016) was born in Monroeville, Ala., where she died a couple of months shy of her 90th birthday. In between, she lived elsewhere and wrote To Kill a Mockingbird in New York City.

In terms of popular acclaim and commercial success, there are striking similarities between the books.

| MORE IN BOOKS | |

| John F. Kennedy: an anglophile for all seasons By Pat Murphy |

|

| Fenians used Canada as an Irish revolutionary pawn By Pat Murphy |

|

| ‘Radical Joe’ Chamberlain inspires new British PM By Pat Murphy |

Gone With the Wind was published in 1936 and became the best-selling American novel of the year. It repeated the feat in 1937.

To Kill a Mockingbird was published in 1960. Between August of that year and June 1962, it spent 98 weeks on the New York Times fiction bestseller list.

And both books were huge, persistent international successes, reportedly racking up sales in excess of 30 million copies each.

Although it’s true that contemporary critics weren’t always kind to the books, that didn’t stop them from winning literary awards. Both nabbed the Pulitzer Prize for Fiction, Gone With the Wind in 1937 and To Kill a Mockingbird in 1961.

And Hollywood came calling for both.

Premiered in Atlanta, on Dec. 15, 1939, the Gone With the Wind movie was an enormous success, domestically and internationally. When it opened in Dublin, Ireland, rail excursions brought people in from rural areas and legend has it that an astonishing 300,000 paid admissions were generated in the first eight weeks. Adjusted for inflation, it remains the all-time global box-office champion.

To Kill a Mockingbird, too, was a substantial cinematic hit. Released at the end of 1962, it earned its cost back many times over and was one of the top North American grossers in its year.

The Academy Awards also showered honours on both movies. Gone With the Wind won eight, while To Kill a Mockingbird scored three. And among the winners were the leading players, Vivien Leigh as Gone With the Wind’s Scarlett O’Hara and Gregory Peck as To Kill a Mockingbird’s Atticus Finch.

If you’re looking for contrasts in characters, you couldn’t do any better.

O’Hara is wilful, self-absorbed and prone to inflicting collateral damage on those around her. Finch, in contrast, is thoughtful, noble and inspirational.

Indeed, the emotional investment many people made in the Finch character caused problems when Lee published her second novel, Go Set a Watchman, in 2015.

Go Set a Watchman presents Finch as something of a bigot. From bravely defending an unjustly accused black man in the 1930s, he has now become an opponent of 1950s federal desegregation laws. Illusions were shattered and feelings were hurt as a result of the novel’s release.

In the real world, of course, moral complexity abounds. It’s completely feasible that an aware and intelligent white man growing-up in the 20th century Deep South could simultaneously believe that blacks should be treated fairly by the justice system – in the sense of not being convicted for crimes they didn’t commit – while also upholding racial segregation. Actual people are multi-dimensional.

As for O’Hara, are there any positive lessons to be taken from her character? Counter-intuitive though it may seem, the answer is probably yes.

Mitchell believed Gone With the Wind was about survival, about how “Some people survive; others don’t.” A term she used was “gumption,” putting it this way: “So I wrote about people who had gumption and people who didn’t.”

It’s an old-fashioned word, dating from the early 18th century. And its persistent relevance to everyday life may go some way toward explaining Gone With the Wind’s sustained appeal across decades and cultures.

To quote the novel’s last line, “After all, tomorrow is another day.” So knuckle down and get on with it!

Troy Media columnist Pat Murphy casts a history buff’s eye at the goings-on in our world. Never cynical – well perhaps a little bit.

The views, opinions and positions expressed by columnists and contributors are the author’s alone. They do not inherently or expressly reflect the views, opinions and/or positions of our publication.