Growing up in government care in Manitoba was difficult. The deep politicization of child welfare didn’t help. Polarized public opinion and a controversy-avoidant government shaped the legislation and policies that affected my day-to-day life.

Growing up in government care in Manitoba was difficult. The deep politicization of child welfare didn’t help. Polarized public opinion and a controversy-avoidant government shaped the legislation and policies that affected my day-to-day life.

Everyone, it seemed, sought to provide me with the best care – but it often missed the mark. Unfortunately, my experiences in the care system aren’t isolated. Instead, they illustrate systemic government failures across the country to provide safe, quality care for youth.

We can – and should – do better. Supporting youth in care with comprehensive supports to age 25 would be an important first step.

Living in care likely ensured me a better outcome than I would have seen if I had remained with my birth mother. Her challenges extend from typical channels: an indigenous woman born to a Manitoba prisoner and adopted out in the 1960s – not a formula known for good outcomes.

So when I asked to be put into care as a young teenager, I was confident I was making the right decision. I craved the support and structure a home could provide. I felt empowered as I took ownership over my care.

The first home did have structure, but it was also riddled with emotional and spiritual abuse. I continued to move through many more placements and social workers.

Many of us kids in care live in dozens of placements.

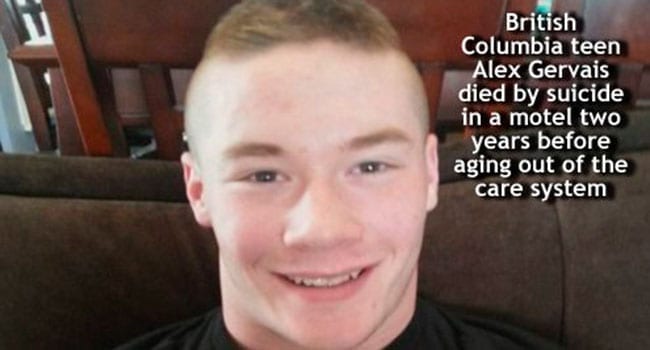

The tragic death of British Columbia teen, Alex Gervais, who died by suicide in a motel just months before aging out of the care system, lived in 17 placements over his life time. Such multiple transitions illustrate government care as a complicated and tumultuous time in the lives of trauma-inflicted youth.

Transitory care experiences leave lasting effects on vulnerable youth.

In Winnipeg, 49 per cent of homeless individuals stated they had spent time in a group home or other Child and Family Services (CFS) placement as a child. This is consistent with Ontario, with 43 per cent of street-involved youth describing Children’s Aid Society (CAS) involvement.

High school graduation rates are dismal: 33 per cent of youth in care graduate in Manitoba, for example, compared to 89 per cent of their peers not in care.

My five years as a minor in care left me with serious mental health challenges and experiences with homelessness. The CFS shelters were full of other youth in care experiencing the same sort of crises.

But somehow, I made it. I didn’t slip through the cracks and I found myself navigating a university degree and multiple jobs. I was always aware of my privilege and luck, but I’m an exception.

In Canada, 60 per cent of young people aged 20 to 24 live at home with their supporting parents. Yet we hold youth with the complex traumas associated with growing up in care to a different standard and expect them to stand alone.

My colleagues almost universally have some sort of support from their parents. But my safety net is small. I have very few people to call upon for housing support, in financial emergencies, and if I was really struggling with mental health or addiction.

Many provinces still drop services for youth in care at age 18 or 21, despite our desperate pleas for help.

Outcomes for young people who age out of care are typically bleak. I felt proud and excited to graduate, but I was one of few youth from care on the convocation stage. Many of us are caught up with other systems; 41 per cent of my B.C. peers have criminal justice system involvement.

These results aren’t surprising. Historically, little support has been given to youth transitioning out of care so they often don’t have the skills they need to survive.

My experience was typically unstable and frustrating. But I still made it. However, I have a benchmark to compare myself to. My twin sister, who entered care at the same point I did, has struggled. Her experiences with homelessness, late graduation and unsafe relationships are consistent with so many other youth from care.

When governments apprehend children and put them in care, they’re assuming a responsibility for ensuring the success of vulnerable children. As a society, we aren’t living up to the promise or the responsibility.

Governments in Canada need to step up and guarantee comprehensive youth in care the necessary supports and services to age 25. It’s an essential first step to levelling the playing field.

Dylan Cohen is an indigenous former youth in care and a project co-ordinator for AgedOut.com in British Columbia. Dylan seeks to create opportunities for youth in/from care across the country through advocacy and public policy justice.

Dylan is a Troy Media Thought Leader. Why aren’t you?

The views, opinions and positions expressed by columnists and contributors are the author’s alone. They do not inherently or expressly reflect the views, opinions and/or positions of our publication.