In these contentious Brexit days in the United Kingdom, it’s strange to remember that there was once a plan for a Franco-British Union.

In these contentious Brexit days in the United Kingdom, it’s strange to remember that there was once a plan for a Franco-British Union.

No, I’m not making that up. However short-lived, the plan was real.

On June 16, 1940, the British cabinet approved a “declaration of indissoluble union” to this effect:

“France and Great Britain shall no longer be two nations, but one Franco-British Union. The constitution of the Union will provide for joint organs of defence, foreign, financial and economic policies. Every citizen of France will enjoy immediately citizenship of Great Britain, every British subject will become a citizen of France.”

In the near-term, a single war cabinet would control both armies. Down the road, the financial responsibility for rebuilding would be a joint effort that pooled resources.

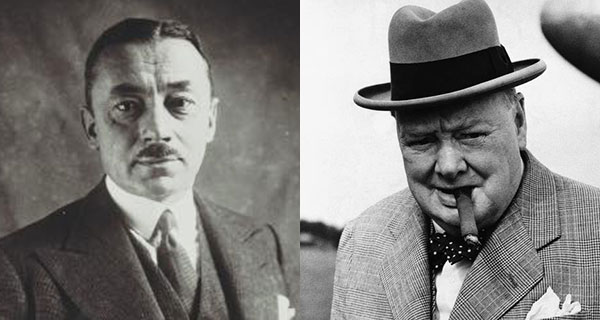

In addition to the endorsement of British Prime Minister Winston Churchill, the idea had the approval of Gen. Charles de Gaulle, then just arrived as a French exile in London. And Paul Reynaud, the French prime minister, was on board.

Variations of the concept had been kicking around in intellectual circles for a while. English luminaries like Arnold Toynbee and Hugh Dalton were interested, as was the Frenchman Jean Monnet. Post-war, Monnet would earn the sobriquet “Father of Europe” for his seminal role in establishing the predecessor of today’s European Union.

Necessity provided the impetus for this extraordinary proposal. The French army was crumbling under the German blitzkrieg and the British were anxious for France to stay in the war. In particular, they wanted to keep the French fleet out of German hands.

The proposal was drafted on June 14, the day the German army entered Paris. Monnet was one of the drafters on the French side.

Initially skeptical, Churchill went along. He later wrote that he was surprised at the British cabinet’s level of enthusiasm for such “an immense design whose implications and consequences were not in any way thought out.”

But desperate times call for desperate measures. So his advice to the cabinet stressed how “we must not let ourselves be accused of lack of imagination.”

De Gaulle’s inclination was similar. A grand gesture was needed and it should be “immediate.” Otherwise, France would surrender and exit the war.

In the afternoon of June 16, de Gaulle and Churchill called Reynaud to pitch the idea. He was receptive. Given his personal preference for France to fight on from North Africa, Reynaud now had a lever to use with his reluctant cabinet.

It was to no avail. The French ministers turned down the proposal.

Suspicion of British motives and historical resentment played parts. So did a sense of futility.

Marshal Philippe Petain, the 84-year-old First World War hero who quickly succeeded Reynaud as prime minister, was especially trenchant. Union with Britain would be the equivalent of “fusion with a corpse.”

From Petain’s perspective, Germany had already won the war and Britain was defeated – even if it hadn’t internalized the fact. Consequently, the thing to focus on was preventing the physical destruction of France and salvaging whatever autonomy was possible. This would entail an armistice with Germany.

In retrospect, many of those who had been on board with the proposal had second thoughts, even seeking to distance themselves from something they’d promoted.

De Gaulle, for instance, said: “It was a myth, made up like other myths by Jean Monnet. Neither Churchill nor I had the least illusion.”

It would be easy to look back on this as a missed opportunity. Had it gone the other way, it could have set the stage for a post-war federal Europe.

That, though, is wishful thinking.

It’s true that Britain, or more specifically England, has a long historical association with France, stretching as far back as William the Conqueror in 1066. As noted in a prior column, even the greatest of English medieval heroes – Richard the Lionheart – was ethnically, culturally and attitudinally French.

But over the last 500 or so years, the two countries have evolved very differently. And had the French government accepted the June 1940 proposal, the resulting union wouldn’t have survived the end of the war.

De Gaulle was both insightful and prescient when he nixed Britain’s initial Common Market application in 1963. Britain, or at least England, doesn’t have its heart in Europe.

Troy Media columnist Pat Murphy casts a history buff’s eye at the goings-on in our world. Never cynical – well, perhaps just a little bit.

The views, opinions and positions expressed by columnists and contributors are the author’s alone. They do not inherently or expressly reflect the views, opinions and/or positions of our publication.