My first awareness of George H.W. Bush dates to the 1970 U.S. midterm elections. He was running for a Senate seat in Texas but – in an era when memories of the Civil War still made statewide office a steep climb for Republicans – he was decisively beaten by Democrat Lloyd Bentsen.

My first awareness of George H.W. Bush dates to the 1970 U.S. midterm elections. He was running for a Senate seat in Texas but – in an era when memories of the Civil War still made statewide office a steep climb for Republicans – he was decisively beaten by Democrat Lloyd Bentsen.

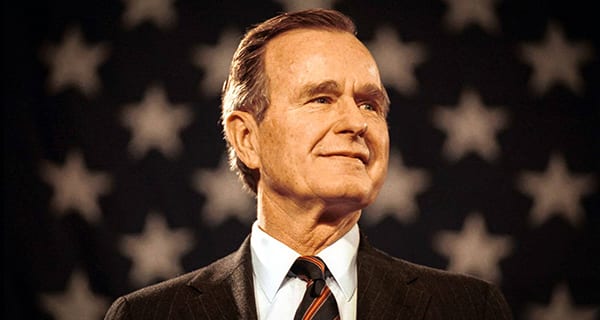

Bush died on Nov. 30 at the age of 94.

The thing that struck me in 1970 about Bush wasn’t the loss, but rather the way in which he tried to position himself as more conservative than he really was. It was an indication of an authenticity problem that would never quite go away. While all successful politicians dissemble, the way Bush did it tended to reinforce rather than assuage doubts.

After 1970, Bush’s next electoral adventure was the race for 1980’s Republican presidential nomination. In between, he’d held a series of prestigious appointments, including U.S. envoy to China and director of the CIA. His resume was being nicely burnished.

And for a moment, his 1980 presidential prospects looked bright.

When Ronald Reagan took Iowa for granted and stayed aloof from the competition, Bush managed to narrowly win the January 1980 caucus vote. Suddenly, he was all over the news as the man with momentum. In an unfortunate preppy turn of phrase, he described himself as having the “Big Mo.”

The weeks immediately following Iowa turned the Republican race upside down. Disparaging talk about Reagan’s age became widespread and Bush – photographed energetically jogging – surged to the front of the polls.

Trouble, however, was lurking. Part of this was out of Bush’s control but part of it wasn’t.

The out of control bit had to do with Reagan’s decision to come down from the clouds and slug it out in the first primary state – frigid New Hampshire. Travelling all over and taking part in debates, Reagan demonstrated that he had few peers and no betters at the business of political campaigning. Viewed up close, he seemed neither too old nor lacking in vigour.

That, though, wasn’t the only problem for Bush.

Other than portraying himself as a prospective winner with an impressive resume, Bush seemed to lack credible substance. To quote political journalist Martin Nolan, “Bush discovered that it is not possible to survive as an ideological chameleon, at least not in New Hampshire.”

Social class came into it, too. Whereas Reagan had an ability to connect with less-affluent voters, Bush could never quite shake the aura of his New England patrician upbringing. Contrasting the backgrounds of local campaign operatives, journalist Mark Shields characterized it as a contest “between Schlitz and sherry, between citizenship papers and collected papers, between night school and graduate school.”

Bush didn’t merely lose resoundingly in New Hampshire, he almost threw away his chance of getting the nod as Reagan’s eventual running mate.

On the Saturday before the primary, a planned debate in Nashua, N.H., turned into an extraordinary piece of political theatre. While it’s fair to say that Bush was thrown a curve ball – “mouse trapped” was the term used at the time – it’s also fair to say that he flubbed it badly.

Played out on stage before a live audience, the controversy was about how many candidates would be allowed to participate. Reagan brought his performing skills to bear and projected a sense of command but Bush seemed to freeze. In the process, he struck Reagan as being the kind of guy who might fold under pressure.

Bush’s behaviour that night puzzled many, including his national political director David Keene. Speaking at a Harvard post-election conference the following December, Keene was at a loss: “Well there are some things you can explain and some things you can’t.”

Still, albeit without enthusiasm, Reagan opted to go with Bush when the time came to make a vice-presidential choice. And over the years they apparently evolved a reasonable relationship, in which Bush acted as a loyal lieutenant, even suppressing his skepticism about Reagan’s outreach to Mikhail Gorbachev.

Elected to the presidency in his own right in 1988, Bush was in large measure winning the third term that age and the constitution foreclosed for the popular Reagan. But left to stand entirely on his own, his political fragility was exposed relatively quickly and he was defeated in 1992.

Perhaps my late father was right. Watching Bush being interviewed on Irish TV during his vice-presidency, my father concluded that he was naturally “a number two man.”

Troy Media columnist Pat Murphy casts a history buff’s eye at the goings-on in our world. Never cynical – well, perhaps just a little bit.

The views, opinions and positions expressed by columnists and contributors are the author’s alone. They do not inherently or expressly reflect the views, opinions and/or positions of our publication.