In a line at the supermarket checkout, I glanced back at the woman who was placing her purchases on the belt behind my grocery items, and I couldn’t help but wonder what life had done to her to put such an expression of tired crabbiness on her face.

In a line at the supermarket checkout, I glanced back at the woman who was placing her purchases on the belt behind my grocery items, and I couldn’t help but wonder what life had done to her to put such an expression of tired crabbiness on her face.

That unpleasant expression, mixed with an obvious impatience at the slowness of the line, certainly didn’t make her face a pleasant one to look at, and I had no reason to glance her way again until the checkout person – a young man with an earring – shared a joke with the shopper he was ringing in, and I heard a burst of laughter from behind me.

Turning, I saw a completely different woman, her face transformed by a cheerful smile as she looked up at me and said, “If he liked that joke, just wait till he sees my credit card.”

The transformation was amazing, almost miraculous. Suddenly the woman with the pinched and crabby expression was someone with whom I felt I could chat, discuss the strange jump in the price of broccoli, and share a mischievous grin when the young man with the earring said to the elderly male shopper ahead of us, “Do you want a hand with your bag?”

I paid for my purchases, said goodbye to the now quite cheerful woman, and, as I walked out to my car, I thought about the way her smile had changed her appearance so dramatically and opened up communication between us. Driving out of the parking lot, I saw the woman emerging from the store, and she actually recognized me behind the wheel, because she gave me a cheery wave.

Driving home, I thought some more about how transformative a smile can be, how it makes communication far more likely, how it makes one feel more generous and caring about someone who would normally not prompt such feelings. And then I began thinking about how few are the smiles of cordiality and genuine friendliness that appear on the faces of Indigenous leaders, how rarely one hears the verbal equivalent of a smile – words of conciliation, friendship or praise from the lips of those who supposedly seek a new relationship with non-Indigenous Canada. Is it wise, I wondered, to maintain an attitude of accusation, blame and complaint when a smile would achieve so much more?

I’m sure many would argue that, with so many serious concerns and suspicions of “white” apathy or oppression, native leaders can hardly adopt a genial attitude when dealing with the oppressors, or – heaven forbid – indicate any pride in being Canadian. The chances of an Assembly of First Nations leader being seen in public with an “I Love Canada” shopping bag are very slim indeed. But think of how much goodwill such a gesture would create.

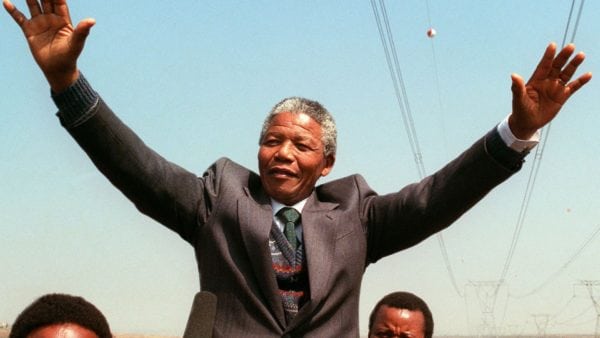

When one thinks of Nelson Mandela, arguably the most successful leader of an oppressed people in the last 100 years, one does not think of a man who was always scowling, always hurling charges of this and that against the white population of South Africa. Much of Mandela’s credibility and authority – and his eventual success – came from the fact that he was able to fight for justice without rancour or vindictiveness. That genial smile of his seemed to show a man who had moved beyond all that – a man who in his openness to others and his focus on the ultimate goal was able to achieve what many had thought impossible, the elimination of apartheid and a freeing of his people. In that, Mandela was truly wise.

North American Indigenous elders are, almost by definition, assumed to be wise. The image of native elders guiding the tribe through difficult times, giving sensible advice about contentious matters, perhaps restraining hotheaded young people, is solidly implanted in many minds, not all of them Indigenous.

And in days gone by, native elders did indeed have a great deal of what could reasonably be called wisdom. If they reached old age, those men and women had years of experience to draw upon, and years of contemplation to make sense of it all. No better source of cautionary words and sound advice was available to people whose lack of a written language prevented them from transmitting to a new generation what had been experienced and what had been learned from that experience. The generally positive results of listening to the elders’ advice earned them respect, even veneration. It was often believed that the elders received their obviously beneficial wisdom from the spirit world.

But no spiritual link is necessary to explain the wisdom of native elders. Put in simple terms, the fact that they had lived longer, seen more, passed on the words of previous elders and thought about things longer, made them the wise men and women of the tribe. And there were times when long experience told them that sometimes it is better to extend a hand of friendship.

But for the most part, the elderly men and women living on the Blood Reserve in southern Alberta or the Peguis First Nations Reserve in Manitoba are not the ones making policy, sending out messages via the Internet, speaking to the media, and sitting down with provincial and federal ministers to hammer out important agreements.

The individuals who do those things are politicians, not wise elders, and they speak, act and negotiate like politicians, their main goal being immediate advantage, not the pursuit of longer-term goals dictated by wisdom. Elected chiefs say and do the things that they believe will please their constituents, which is to say, the people whose votes will keep them in office.

It’s as if the revered Blackfoot chief Crowfoot sensed that his people wanted to join the Riel Rebellion and proudly announced his tribe’s intention to support that ill-fated uprising. His refusal to involve his tribe was at the time criticized as cowardice, but today Crowfoot’s decision is usually mentioned when references are made to his wise leadership.

We live in a time when wise leadership might very well lead to real change and what’s being called reconciliation. But are the strategies employed by native leaders the wisest approach?

I once had a very good conversation with my father, during which I argue heatedly for a particular social program that I thought was a very good idea. My father listened patiently as I outlined my reasons and then said to me: “You can have all the good ideas you want, but if you can’t get people to accept them, you had better think again.”

Native leaders, activists and their supporters seem totally blind to the fact that their demands, their often hostile declarations, combined with repeated accusations and complaints, simply don’t wash with the Canadians who really count: the voters. Whether the voters are ill-informed or self-absorbed or racist is beside the point. They are a reality that wise Indigenous leaders would recognize and consider when formulating policy or making arguments. Winning over the majority of Canadian voters will not be easy, but continually making strident accusations, claims and demands is hardly the way to do it.

It would be hard for a genuinely concerned native leader to pull back from policies or strategies that demand action on poverty, lack of education and other challenges that today face tribal members, but is aggressively pressing for immediate remedy of all those problems while hurling accusations of racism and colonial oppression the wise course? Do confrontational stances on issues like pipeline expansion suggest wisdom? Is creating a greater divide between Indigenous and non-Indigenous Canadians likely to benefit their people in the long run?

The prime minister and his cabinet know that there are children in Canada who suffer from malnutrition or a lack of medical care, but few Canadians would expect Ottawa to simply pour billions of dollars into a fund that would feed every child properly or provide doctors and nurses in every tiny community. Providing immediate assistance for some disadvantaged segments of our population cannot come before attention to wider national concerns, an attention that makes things better in the long run, and experience tells us that providing lots of short-term funding is rarely the best way to ensure a healthy economy and long-term prosperity for all.

Canadian voters may vote for the party that seems to offer the most short-term benefits, but they do so in the belief that the men and women they send to Ottawa will not bankrupt the country in providing them. And federal politicians once elected usually take the long-term approach, which explains why elections promises, if kept, are so often watered-down, and why Canada has always been seen as a fairly moderate country. And a relatively happy and prosperous one at that.

While CBC Radio guests and contributors to the Globe and Mail may appear totally on board with the arguments being made for Indigenous self-government, a reworking of the nation’s legal system, power to halt industrial development, a renaming of buildings and streets, and a banishing to purgatory of anyone suspected of cultural appropriation or racial denigration, the average Canadian voters will simply not accept significant changes to a society they know and have faith in. This non-Indigenous Canadian will presumably be called arrogant for urging Indigenous leaders to abandon or at least modify their current approach, lest they find themselves dealing with a federal government that is far less concerned about native issues, and far more intransigent when it comes to negotiating treaties or land ownership.

I believe wise native elders would see the likelihood of such a thing and plan accordingly, just as Crowfoot, described by historian Hugh Dempsey as “a wise and farsighted chief,” looked beyond immediate advantage and discouraged the traditional stealing of horses from the Crees. Dempsey writes that “From this first meeting [in 1874], there was a feeling of friendship and trust between Crowfoot and [NWMP Colonel James] Macleod,” a relationship that proved of great benefit to the Blackfoot.

Some would say that only by constantly pressing for change, constantly attacking the status quo, constantly pointing to past injustices, will Indigenous people emerge from the second-class citizenship to which they now seem condemned. But the manner in which that pressure is exerted counts for a great deal. Those old enough to remember the 1960s will recall that not every protest against the Vietnam War or racial discrimination was peaceful, persuasive and positive in its results. The Black Panthers and the Weather Underground remind us that extreme positions often hurt the cause for which people are fighting. An environmental protest that turns violent may demonstrate the passion of the protestors for their cause, but it may also confirm people’s beliefs that environmentalists are nothing but a bunch of anti-social nutcases.

With each deeply partisan demand, Canada’s Indigenous people are being turned into a political party, increasing division within the country.

And of course, politicians are not saints. Many act out of pure self-interest, attempting to solidify or increase their power and prestige.

This is not wise leadership. Some would say it is pure folly. But it doesn’t have to be this way.

As Nobel Peace Prize recipient Mother Teresa said, “We shall never know all the good that a simple smile can do.”

A retired literacy coach and teacher of English, Mark DeWolf is a writer and musician living in Halifax. He’s writing a memoir of his childhood on the Blood (Kainai) Reserve in southern Alberta, and is a research associate at the Frontier Centre for Public Policy.

The views, opinions and positions expressed by columnists and contributors are the author’s alone. They do not inherently or expressly reflect the views, opinions and/or positions of our publication.